Esmail Yazdanpour

Few nineteenth-century English novelists have enjoyed a reception in Iran as wide and enduring as that of Jane Austen. For decades, her novels have been repeatedly translated, reprinted, and read by generations of Iranian readers, particularly women, who have found in her restrained prose, moral intelligence, and attention to everyday life a familiar and deeply resonant voice. Austen’s focus on family, marriage, economic vulnerability, and the subtle negotiations of social power within domestic space has allowed her works to cross linguistic, cultural, and historical boundaries. In Iran, she is often read not simply as a canonical Western author, but as a writer whose narratives of constraint, dignity, and quiet resistance speak directly to lived experience in a society shaped by strong social norms and gendered expectations.

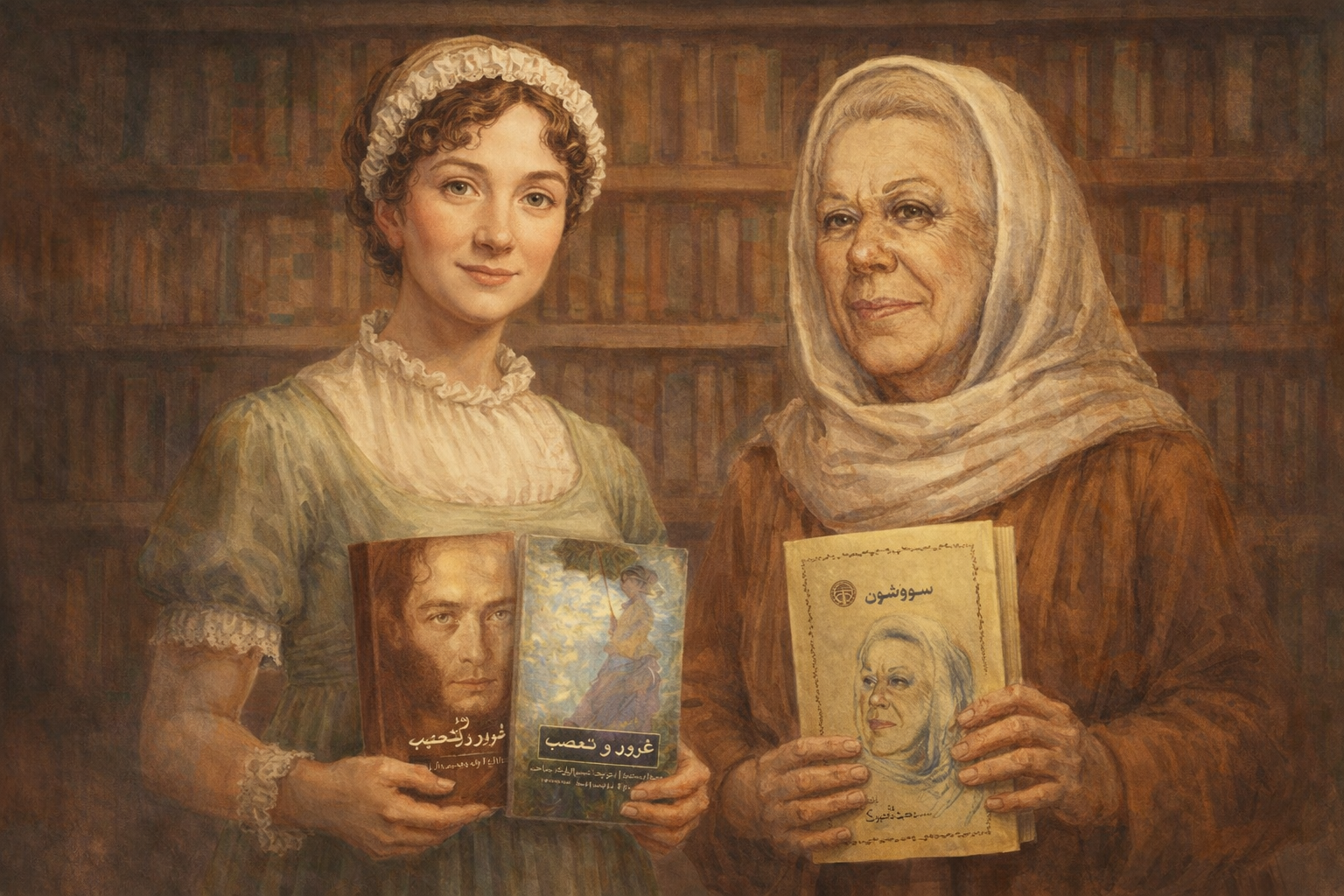

What connection exists between Jane Austen’s rectory in Steventon and the world of Simin Daneshvar’s stories in Suvashun? On the 250th anniversary of Austen’s birth, this article traces a path from the heart of English literature to the works of Iranian female writers, revealing how a focus on “domestic space” and “everyday details” became a fundamental and effective tool for social critique in both contexts.

December 16, 2025, marks the 250th anniversary of the birth of Jane Austen, a writer who, despite the passage of two and a half centuries, remains one of the central pillars of world literature and one of the most vibrant cultural voices in the English-speaking world and beyond. Born in 1775 in a rectory in Steventon, Hampshire, Austen created a compact body of literary work comprising six complete novels and a number of juvenile writings and unfinished fragments. However, the scope of influence of these works has far exceeded their physical volume, generating a continuous stream of criticism, adaptation, and reinvention over the centuries.

As the literary world celebrates this anniversary, academic and public enthusiasm for understanding and rereading Austen shows no sign of abating. From her devoted fans, known as “Janeites,” who attend festivals in Bath and Hampshire dressed in Regency-era clothing, to Marxist and post-colonial critics who scrutinize the economic and imperialist structures hidden behind the aristocratic mansions of her stories, Austen remains a center of cultural controversy and admiration. The year 2025 sees extensive events worldwide. Special exhibitions such as “A Vivid Mind: Jane Austen at 250” at the Morgan Library in New York and numerous festivals at the Jane Austen House Museum in Chawton testify that Austen is a global phenomenon. But beyond the celebrations and symbolic commemorations, this anniversary is a unique opportunity to reassess her standing—not just as a writer of romances and “happy endings,” but as a keen observer of a world in transition.

Austen wrote on the cusp of the modern era, a time when England was embroiled in long wars with Napoleonic France and facing fundamental changes brought about by the Industrial Revolution. Yet, her novels famously remain silent on “great historical events,” focusing instead on “three or four families in a country village.” This comprehensive research report has been compiled to offer a deep and multifaceted analysis for this anniversary. We begin with her biography and historical context, examine her role in constructing English culture, and then enter the complex realm of literary criticism to explore the views of prominent critics such as Virginia Woolf, Raymond Williams, and Terry Eagleton. We continue by examining the hidden layers of imperialism in her works, citing Edward Said, and finally conclude with an investigation into the fascinating phenomenon of the “Iranian Jane Austen” and a comparative comparison between Austen’s “domestic realism” and contemporary Iranian female writers such as Simin Daneshvar, Zoya Pirzad, and Parinoush Saniee.

Austen’s enduring importance, as Virginia Woolf noted, lies in her “incandescent mind”; a mind capable of consuming obstacles and gender and social limitations to create art that is transparent, unadorned, yet profoundly complex. Reading Austen in 2025 means engaging with the ghosts of empire, class rigidity, early feminist struggles, and the cross-cultural echoes of women who have taken up the pen under the constraints of patriarchy.

The life of Jane Austen (1775–1817) coincided with a period of immense political and social turbulence. Although the Regency of the Prince of Wales officially lasted from 1811 to 1820, the term “Regency Era” refers to a broader timeframe characterized by the transition from the traditional, land-based values of the 18th century to the commercial and industrial realities of the 19th. The England in Austen’s novels appears ostensibly stable; a world of ballrooms, rectories, and landscaped parks. But this stability was an artistic illusion maintained against a backdrop of the French Revolution, the rise of Napoleon, and internal unrest. Enclosure Acts were changing the face of the countryside and privatizing common land, transforming the social structure of rural communities. The class system, though seemingly rigid and impenetrable, was permeable to “money”—a subject Austen addresses with ruthless precision. The aristocracy or “gentry” to which Austen belonged was not a monolithic block, but a stratified layer anxious about its status.

Austen’s personal life reflected the instability of this “pseudo-aristocracy.” As the daughter of a clergyman, she lived on the fringes of the wealthy elite; she possessed the education and manners of the aristocracy but lacked their financial independence. After her father’s death, she, along with her mother and sister Cassandra, became financially dependent on her brothers. This situation, known as “genteel poverty,” deeply influenced the economic anxiety prevalent in her stories. Knowing the exact annual income of characters in Austen’s novels—for example, £5,000 for Mr. Darcy or £400 for an ordinary clergyman—is not due to superficial materialism, but represents vital data for survival in her world.

| Character / Person | Source of Income | Annual Income (Est. 1810 £) | Approx. Modern Equivalent ($/£) | Social Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jane Austen | Sale of novels (Lifetime) | Avg. annual < £50 (from writing) | ~$67,000 (Lifetime total earnings) | Genteel poverty, dependent on family |

| Mr. Darcy (Pride & Prejudice) | Estates and Investments | £10,000 | ~£300,000 – £500,000 (Very high purchasing power) | Wealthy Aristocracy (The 1%) |

| Mr. Bingley (Pride & Prejudice) | Trade (New Money) | £4,000 – £5,000 | ~£150,000 – £200,000 | Emerging affluent middle class |

| Mr. Bennet (Pride & Prejudice) | Estate (Entailed/Limited) | £2,000 | ~£80,000 | Local Gentry |

| Dashwood Family (Sense & Sensibility) | Limited Inheritance | £500 (for 4 people) | ~£20,000 | Relative poverty within the gentry |

| Rural Laborer | Daily Wages | £15 – £20 | ~£600 – £800 | Absolute poverty |

As seen in the table above, the class gap was enormous. Austen herself, compared to characters like Darcy, was in a very fragile financial position, and her income from writing during her lifetime was meager (about £684 for four novels published during her life). This justifies her sharp, realistic view of marriage as an economic contract.

Understanding Austen’s works is impossible without recognizing the legal status of women in that era. Under the law of “Coverture,” which remained in place until the late 19th century, a woman’s legal identity was merged into her husband’s upon marriage. Married women had no right to independent property, could not sign contracts or write wills, and all their movable property and income belonged to their husbands. This legal reality explains the heavy pressure placed on characters like Elizabeth Bennet or the Dashwood sisters. For a woman of Austen’s class, there were only two ways to ensure economic security: marriage or inheritance (the latter often going to sons due to primogeniture laws). “Remaining single” meant permanent and often humiliating dependence on relatives, a fate symbolized by the character Miss Bates in the novel Emma. Thus, Austen’s focus on marriage is not a romantic preoccupation, but a vital survival strategy against social and economic erasure.

Austen’s artistic maturity is usually divided into two periods: the early novels drafted in the 1790s (Northanger Abbey, Sense and Sensibility, Pride and Prejudice) and the later, more mature novels written or rewritten in Chawton (Mansfield Park, Emma, Persuasion).

Austen’s great technical innovation was the masterful use of “Free Indirect Discourse.” This technique allowed her to blend the narrator’s voice with the character’s inner thoughts without using quotation marks or phrases like “she thought.” This was a key tool for creating the “domestic realism” that later became the hallmark of the 19th-century English novel, allowing readers to share the characters’ subjectivity while maintaining an ironic distance.

Over the past 250 years, Jane Austen has become more than just an author; she is a metaphor for “Englishness.” Her image on the £10 note, countless BBC adaptations, and literary tourism in Bath and Hampshire all indicate her status as a national “cultural asset.”

In her 250th anniversary year, the “Austen Industry” is more active than ever. Festivals like the “Pride and Prejudice Festival” and “Regency Balls” in Bath link Austen with a nostalgia for the pre-industrial era; a time when propriety, etiquette, and fine clothes seemed to prevail over the violence of reality. However, this commodification often hides the critical edges and bitter satire of her works. The “Austenmania!” exhibition at the Jane Austen House Museum, looking back at the 1995 adaptations (especially the Pride and Prejudice series starring Colin Firth), attempts to explore this complex relationship between the original text and the public image constructed by media. These celebrations also reveal a cultural paradox: Austen, who was a critic of social hypocrisies in her time, has now become a symbol for cultural conservatism and longing for the past. Yet, as we shall see in the following sections, modern academic and critical readings are challenging this “safe” and “cozy” image of Austen.

To understand the true depth of Austen’s works, one must move past the surface and public celebrations to the views of prominent literary critics who have pulled her out of the “drawing room” and placed her in the arena of literary theory.

Virginia Woolf, the 20th-century modernist writer, had a deep and personal engagement with Jane Austen. In her seminal book, A Room of One’s Own, Woolf identifies Austen as one of the few women who achieved the condition of “genius.”

Woolf argues that to create great art, the writer’s mind must be “incandescent”; meaning it must burn away all personal obstacles, anger, and bitterness to create a work free from the writer’s gender and personal grievances. Woolf believed that many female writers (like Charlotte Brontë) allowed their anger at social restrictions to deform the structure of their novels. But Austen, like Shakespeare, was able to write “without hate, without bitterness, without fear, without protest, without preaching.” This “incandescent mind” allowed Austen to create a complete and perfect world despite living in a restricted environment.

In an essay titled Jane Austen (1925), Woolf rejects the idea that Austen was merely a writer of surfaces. She writes:

“Jane Austen is thus a mistress of much deeper emotion than appears upon the surface. She stimulates us to supply what is not there. What she offers is, apparently, a trifle, yet is composed of something that expands in the reader’s mind…”

Woolf believes that Austen’s silence and brevity are her strengths. By focusing on mundane details—a dance, a dinner, a conversation in a carriage—Austen implies the tragedies and passions hidden beneath the skin of society. Woolf also looks with regret at Persuasion, surmising that had Austen lived longer, she likely would have pioneered the style later perfected by Henry James and Marcel Proust; a style with less dialogue and more internal reflection.

While Woolf focused on psychological and aesthetic aspects, Raymond Williams, the prominent Marxist critic, turned the lens of criticism toward social and economic structures in his important work The Country and the City.

Williams introduces the concept of the “knowable community” to describe the social world of the novel. He argues that in Austen’s novels, “neighbors” are not those physically living nearby, but those who are socially visitable. This network of estates and families forms a “tight mesh” through which the vast majority of the population—laborers, servants, and the poor—fall out and become effectively invisible. For Williams, Austen’s achievement is the precise delineation of this selected “knowable community.” The moral drama of Emma or Pride and Prejudice is only possible based on the stability of this class structure; a structure that extracts wealth from the land (and colonies) without ever showing the suffering and labor that produces it. Williams compares this approach to later writers like George Eliot, who tried to expand the scope of the “knowable community” to include the lower classes.

Williams also points to the “magical” nature of money in Austen’s works. Wealth is vital in these novels, but its origin is often vague or “settled.” Incomes appear as “£5,000 a year,” detached from the agrarian exploitation or urban speculation that produced them. Austen is the chronicler of a class busy with “improving” estates and enclosing lands, a process Williams sees as the vanguard of agrarian capitalism.

Terry Eagleton, another Marxist critic, builds on Williams’s views but offers a sharper ideological critique. In The English Novel: An Introduction, Eagleton views the novel form as a bourgeois tool designed to negotiate and resolve conflicts between the old aristocratic order and the rising middle class.

Eagleton argues that Austen’s works represent a historical “settlement” or compromise. Her novels often end with a marriage between the vitality and morality of the middle class (like the Gardiners in Pride and Prejudice or the naval officers in Persuasion) and the stability and tradition of the landed aristocracy (Mr. Darcy, Sir Thomas Bertram). This union is necessary to revitalize an aristocracy in decline and to contain the anarchic energy of new money.

Eagleton is skeptical of the idea of an “organic society” often attributed to Austen’s world. He suggests that this “organic” unity is an illusion or nostalgia for a past that never truly existed. The “organic” village in Austen is actually already possessed by capitalist relations. The “peace” and tranquility in her novels are not a natural state, but a hegemonic construction maintained by the repressive atmosphere of the Napoleonic Wars; an atmosphere that, while absent from the text, exerts invisible pressure on the narrative’s borders. For Eagleton, Austen’s style—balanced, ironic, and rational—is a political act attempting to impose order on a chaotic world.

No critical intervention in Austen studies has been as controversial and influential as Edward Said’s chapter on Mansfield Park in Culture and Imperialism (1993). Said moved the discussion from the domestic interior of England to the geopolitical arena, arguing that Austen’s “two inches of ivory” was carved from the ivory of empire.

Said points out that Mansfield Park is unique among Austen’s novels because it has an explicit structural dependence on the West Indies. Sir Thomas Bertram, the patriarch, is absent for a significant portion of the novel because he must attend to his estates and plantations in Antigua. Said argues that the moral and economic stability of the English manor (Mansfield Park) is directly dependent on slave labor in the Caribbean plantations. Without the income from sugar and slavery in Antigua, the order and prosperity of Mansfield would collapse.

The core of Said’s argument revolves around a specific scene in the novel where Fanny Price, the shy and moral heroine, tells her cousin Edmund about a question she asked Sir Thomas:

“But I did talk to him more than I used. I loved to hear him talk of the West Indies. I could listen to him for an hour together. It entertained me more than all the rest… did not you hear me ask him about the slave trade last night?… I was in hopes the question would be followed up by others… but there was such a dead silence!”

For Said, this “dead silence” is symbolic. The family—and by extension, the novel and the culture—cannot speak about the origins of their wealth. This silence is not just social awkwardness; it is a structural necessity. Acknowledging the brutality of the slave trade would shatter the polite, civilized veneer of Mansfield Park. Said concludes that Austen assumes empire as a natural and given reality, viewing domestic English order as a mirror of imperial order. Sir Thomas’s authority, challenged by his children during his absence, is restored only after his return from “ordering” affairs in Antigua.

In recent decades, a fascinating critical comparison has emerged linking Jane Austen to a generation of Iranian female writers. This comparison goes beyond the superficial label of “romance writing” and addresses the shared use of “domestic realism” as a strategy for survival and resistance against patriarchal structures. Titles such as “The Iranian Jane Austen” have often been applied to writers like Simin Daneshvar, Zoya Pirzad, and Parinoush Saniee.

Just as Austen wrote from the “drawing room” because it was the only space accessible to her as a woman where she could observe, Iranian female writers have often focused on the domestic interior. In a society where the public sphere has often been under male control and strict laws (both before and after the 1979 revolution), the home becomes a “compelling stage” where creativity and repression occur simultaneously.

This “domestic realism” is not a retreat from politics, but a redefinition of the political. By focusing on the details of daily life—cooking, cleaning, raising children, and the meaningful silences of unspoken desires—these writers challenge the “grand narratives” of revolution and war, which are usually dominated by men.

Simin Daneshvar (1921–2012) is often recognized as the pioneer of this movement. Her masterpiece, Suvashun (1969), is set in Shiraz during the Allied occupation of Iran in World War II. Although the novel is deeply political, all events are narrated through the eyes of “Zari,” a wife and mother trying to keep her family safe from the chaos outside.

Comparison with Austen: Like Austen, Daneshvar uses the domestic lens to observe macro-historical events. Zari’s struggle between “prudence” (protecting the family) and “courage” (Yusof’s struggle) recalls the dialectics of Sense and Sensibility or Persuasion. However, unlike Austen’s silence on the Napoleonic Wars, in Suvashun, the walls of the house are permeable, and military occupation directly enters the privacy of the home. Zari’s transformation from a cautious housewife to a political activist at the end of the novel reflects the internal maturity of Austen’s heroines, but with more explicit national and political stakes.

The writer with the greatest stylistic resemblance to Austen is Zoya Pirzad, particularly in her novel I Will Turn Off the Lights (published in English as Things We Left Unsaid).

Narrative: The novel tells the story of Clarice Ayvazian, an Armenian housewife in Abadan in the 1960s. The plot is minimalist and “nothing special happens”; the story revolves around daily routines, neighborhood gossip, and a vague, unfulfilled emotional attraction to a new neighbor.

The novel Sahm-e Man (known in English as The Book of Fate) by Parinoush Saniee offers another parallel. The story of a woman whose life is determined by Iran’s political upheavals (from the revolution to the war) serves as a counterpoint to Austen’s Persuasion.

Comparison: Both works grapple with themes of “regret” and “second chances” (or the lack thereof). Although Saniee’s work is sometimes criticized for being more sociological and less literary (a charge sometimes leveled at Austen by those who miss her irony), it demonstrates the universality of the “marriage plot” as a mechanism for social critique. In both societies (19th-century England and contemporary Iran), a woman’s fate is inextricably linked to her marriage, making “romance” a vital issue for economic and social survival.

| Feature | Jane Austen (19th Century England) | Iranian Female Writers (20th/21st Century) |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Setting | Drawing Room / Aristocratic Mansion | Kitchen / Home Interior / Neighborhood |

| Focal Point | Marriage Market, Etiquette, Morality | Family Dynamics, Impact of Politics on Home, Identity |

| Relation to History | “Dead Silence” (War/Empire in background) | Direct Impact (Revolution/War enters the home) |

| Style | Irony, Free Indirect Discourse | Realism, Stream of Consciousness, Silence/Symbolism |

| Key Texts | Pride and Prejudice, Mansfield Park | Suvashun, I Will Turn Off the Lights (Things We Left Unsaid) |

| Critical Approach | Class Compromise (Eagleton), Imperialism (Said) | Critique of Patriarchy, Censorship, Tradition vs. Modernity |

As we celebrate the 250th anniversary of Jane Austen’s birth, we rediscover her not merely as a fixed statue in the museum of “Merry England,” but as a dynamic force and a multifaceted prism in world literature. Her works are a window through which we can reread the anxieties of early modernity, the hidden structures of empire, and women’s ongoing struggle for independence. Contemporary critical readings have well demonstrated the depth of this view: through Virginia Woolf’s lens, Austen is an artist with an “incandescent mind” who overcame personal anger and limitations to create a perfect form; through the structuralist analyses of Raymond Williams and Terry Eagleton, we understand the class compromises and rigid social boundaries of her world; and through Edward Said’s radical critique, we confront the heavy silences of imperialism that underpinned the apparent prosperity of the West. Finally, the lens of Iranian literature recognizes the enduring power of “domestic realism” as a powerful strategy for women in societies under patriarchal constraints.

The term “Iranian Jane Austen” is not just a mimetic or accidental label, but testimony to the cross-cultural power of her literary form. This pattern shows how focusing on domestic space, etiquette, and everyday details—whether in 19th-century Steventon or 20th-century Abadan—remains one of the most radical methods for critiquing political grand narratives and exposing hidden social repressions in favor of celebrating the essence of life. Closely observing “three or four families in a country village” (or a small neighborhood) remains a method for narrating the world with all its complexity and cruelty. 250 years after her birth, Jane Austen is present everywhere, critiqued, and profoundly—perhaps more dangerously than ever—”relevant.”